News that an arctic fox from Svalbard, Norway, traveled 3,506 km across the sea ice to Ellesmere Island, Canada surprised social media, but not Dr. L. E. Carmichael. The Ontario author of children’s science books is also a scientist whose research revolved around the movements of these plucky little voyagers.

News that an arctic fox from Svalbard, Norway, traveled 3,506 km across the sea ice to Ellesmere Island, Canada surprised social media, but not Dr. L. E. Carmichael. The Ontario author of children’s science books is also a scientist whose research revolved around the movements of these plucky little voyagers.

Carmichael’s PhD, on the population genetics of wolves and arctic foxes, received a Governor General’s Medal at the University of Alberta in 2006. “In those days, the record for long-distance travel in arctic foxes was around 1,000 km,” Carmichael said. Does that mean that today’s foxes are traveling further? Not necessarily. Before the development of modern satellite collars, animal migrations were measured with ear tags, plastic “earrings” with identification numbers on them. “You’d catch a fox and tag it, then release it to do its thing,” she said. “Then you’d wait months or years for the fox to be recaptured somewhere else.” This method gave scientists a starting point and an end point for the animal’s journey. Since there was no way to know where the fox went along the way, researchers underestimated, assuming that it traveled in a straight line from point A to point B.

With the new satellite technology, however, Norwegian researchers were able to log the fox’s movements throughout her entire journey, revealing not just the distance she traveled, but the precise path she followed – a path that emphasizes the importance of sea ice in the migration.

The record-setting fox in this study was a young female, who may have been looking for a new territory in which to breed. “When foxes born in one area breed in another location, they transfer their DNA from place to place,” Carmichael said. This gene flow was the focus of her research, which revealed very few genetic differences between fox populations that are seasonally connected by sea ice – including those in Canada and in Svalbard. “The ironic thing is that I was encouraged to include Svalbard foxes in my research because they lived so far from Canada, and people thought they’d be genetically distinct. Of course, this new research shows exactly why that isn’t the case.”

Carmichael was also excited to note that the new study’s lead author, Dr. Eva Fuglei of the Norwegian Polar Institute, is someone she collaborated with while completing her PhD. “Dr. Fuglei is brilliant and dedicated and was very supportive of me as a young woman in science,” Carmichael said.

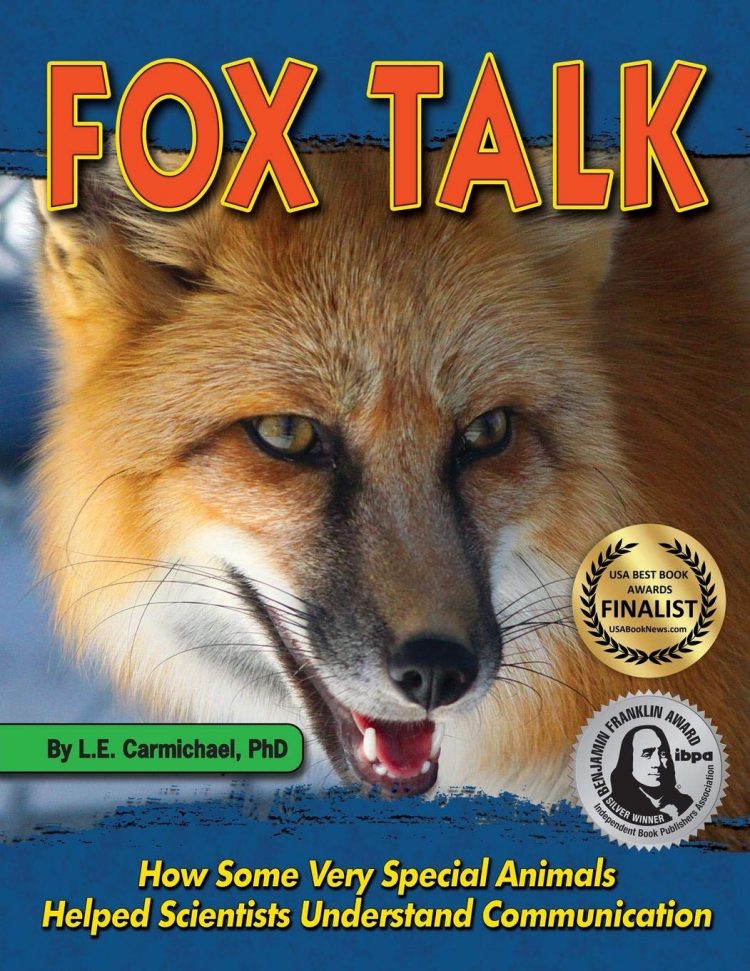

Carmichael is the author of more than 20 science books for children and teenagers. Her 2013 release, Fox Talk: How Some Very Special Animals Helped Scientists Understand Communication, won a Benjamin Franklin Award and a Gelett Burgess Honor. It’s also the subject of presentation called “Decoding Domestication,” which Carmichael offers at schools and libraries across the country. A second title, Fuzzy Forensics: DNA Fingerprinting Gets Wild, won the Lane Anderson Award for best Canadian children’s science book in 2014. Her newest book, The Boreal Forest: A Year in the World’s Largest Land Biome, will be available May 5, 2020, from Kids Can Press.

More information on Carmichael’s work is available at her website, www.lecarmichael.ca. In Ontario, requests for school and library appearances can also be directed to www.authorsbooking.com