Me and Timber, who is 30% Malamute, 70% wolf, and 100% snuggle.

Behaviour is what you do, culture is how you do it.

This is totally obvious in human cultures, which have rules and guidelines for every behaviour – from table manners to what we wear to how we greet each other. But in the last few decades, scientists have begun to realize that animals have culture, too.

And we’re not just talking about primates.

A recent National Geographic’s Weird Animal Question of the Week deals with accents and dialects in animal communication. One of their examples is wild canines, whose howls are not only distinctive between species – grey wolves and coyotes – but are also characteristic to particular geographic regions and populations. These differences probably help animals identify members, not just of their own family groups, but of their broader regions.

The article mentions the long, single pitch howl of the arctic wolf, a group I studied during my PhD research on the genetics of wolves and arctic foxes. My work focused on gene flow, the transfer of genetic material from one population to another. For gene flow to occur, an animal must do two things:

1) Leave the population it was born in

2) Find a mate in a new geographic region, thus passing its genetic material into the next generation.

I discovered there was very little gene flow between tundra wolves and wolves living below the tree line, even though there were no physical impediments to travel between the areas. More surprising, there were several distinctive populations of wolves on the tundra, signalling low gene flow even among wolves living in what was apparently the same habitat.

Or was it?

What I’d stumbled on turned out to be another signal of animal culture – hunting behaviour. All wolves hunt, but what they hunt varies. It has to, because different prey species prefer different habitats. Wolves below Canada’s tree line, for example, eat deer and moose – animals that tend not to move around much. Wolves in the tundra mostly eat barren ground caribou – animals famous for their long-distance migrations. And wolves in the tundra were sorting themselves into populations that corresponded with the migration ranges of their prey.

What this suggests is that wolves are doing more than passing distinctive dialects down to their young. They are teaching their pups how to hunt particular food types. And once the pups learn effective hunting strategies, they tend to stay in an area where they can use those strategies. Because tundra wolves are most often mating with other tundra wolves, their genes as well as their behaviour will diverge from those of wolves in other areas.

Culture – one more thing that does NOT separate humans from animals. 🙂

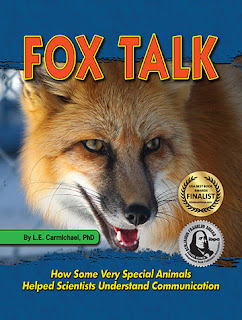

Interested in learning more about animal communication? Check out Fox Talk: How Some Very Special Animals Helped Scientists Understand Communication.