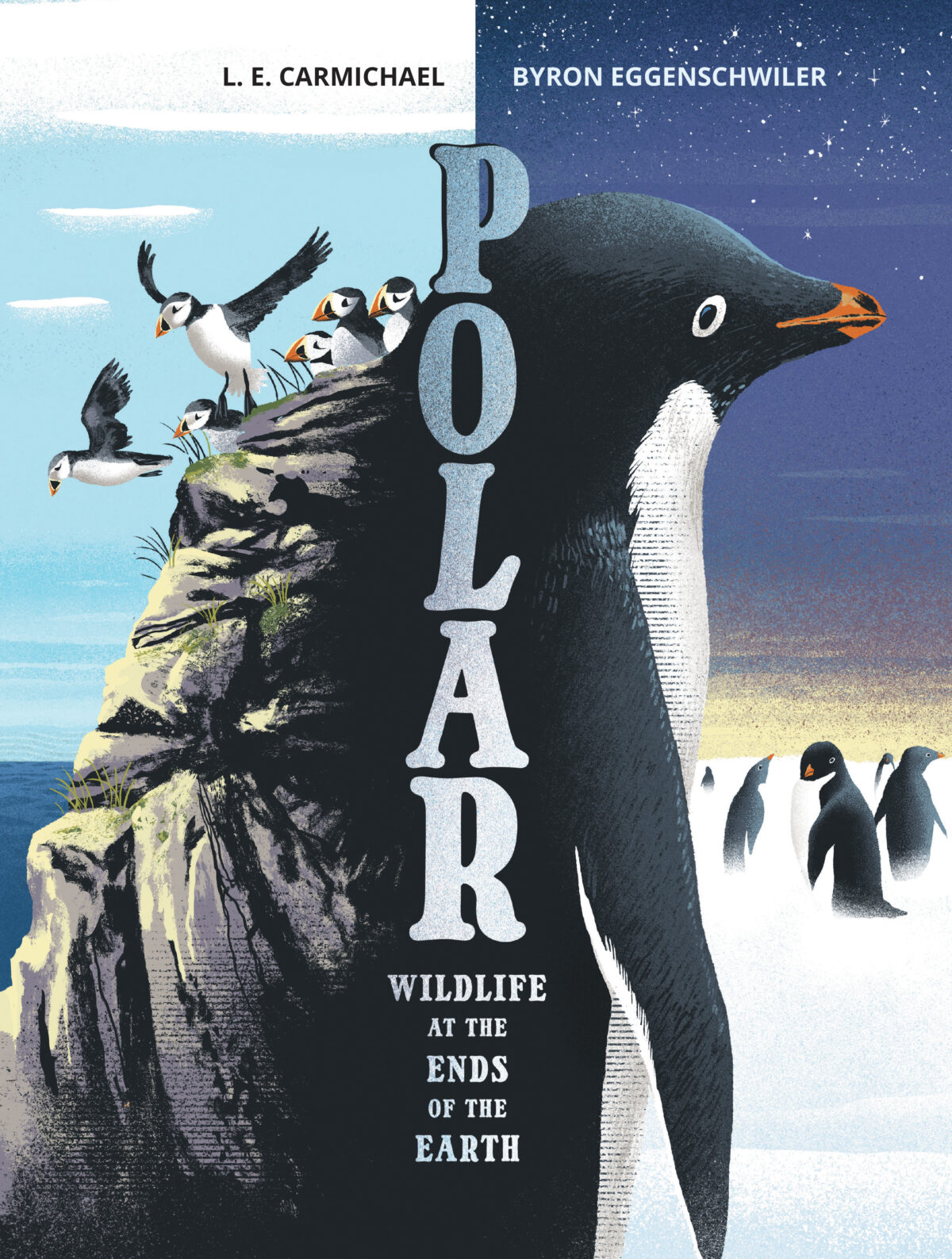

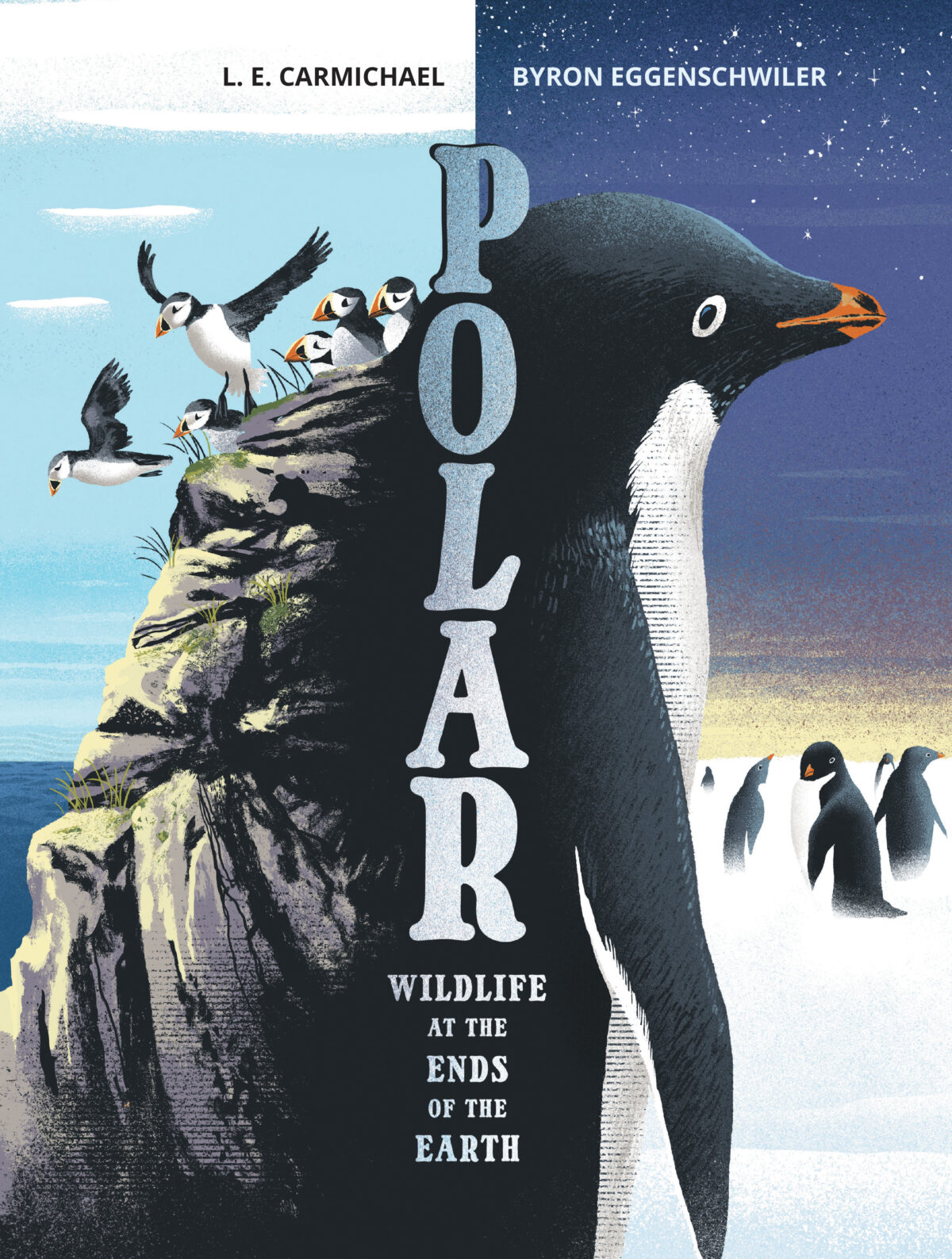

An NCTE Orbis Pitcus Recommended Book

Polar: Wildlife at the Ends of the Earth

From the author of the critically acclaimed The Boreal Forest, a stunning exploration of the animals that have adapted to survive in Earth’s harsh polar regions.

From the author of the critically acclaimed The Boreal Forest, a stunning exploration of the animals that have adapted to survive in Earth’s harsh polar regions.

Publishing under the name L. E. Carmichael, Lindsey is the award-winning author of over 20 non-fiction books for children and young adults. Whether writing about forensics, medicine, animals and the environment, or engineering and technology, Lindsey specializes in making science engaging, relevant, and above all, fun. Teachers, librarians, and parents across North America use Lindsey’s books to spark excitement for STEM in students of all ages.

Lindsey has a PhD in wildlife genetics and worked as a forensic scientist before becoming a children’s writer. Drawing on 20 years’ experience teaching both science and writing, her school visits encourage participation and experiential learning. She is also a popular speaker at conferences, writing workshops, and professional development sessions for adults.

Video games today are more advanced than ever. Players can explore virtual worlds. They can play with friends online. But how do video games work? What are the parts inside a game console?

Programs and apps make computers useful. They let you do homework on laptops. They let you play games on smartphones and tablets. What programs and apps are the most important? Who makes them?

Explains how humpback whales live and grow; discusses their migration, its purpose, and its route; and lists threats humpback whales may face on their migration.

Explains how locusts live and grow; discusses their migration, its purpose, and its route; and lists threats locusts may face on their migration.

From the author of the critically acclaimed The Boreal Forest, a stunning exploration of the animals that have adapted to survive in Earth’s harsh polar regions.

The Arctic and Antarctica, at opposite ends of the Earth, have much in common: bitter cold, ferocious winds and darkness lasting six months. Despite these harsh conditions, many animals have adapted to stay alive in the polar regions. This evocative and beautifully illustrated book from the award-winning team of author L. E. Carmichael and illustrator Byron Eggenschwiler explores how animals at opposite ends of the Earth survive using similar adaptations. There’s the arctic fox who is protected from the ice by the fur on the soles of her feet, the emperor penguins huddling in groups around their chicks to keep everyone warm, and the narwhal using echolocation to find a crack in the surface ice to breathe. It’s a fascinating journey through a year in the polar regions, where animals don’t just survive – they thrive!

Each spread in the book is devoted to a month and includes a themed introduction and two stories on opposites pages, one about an animal in the Arctic and one about an animal in Antarctica. Extra spreads cover topics such as seasons, winter weather and types of ice. The book concludes with a timely description of the disruptions that climate change is causing to the polar regions, and how this will have global consequences. A glossary, further reading, author’s sources, an index and ideas for what children can do to help are included. There are strong life science curriculum applications here in animal habitats and animal adaptation, migration, hibernation and cooperation.

Click here to download the free Teachers’ Guide from Kids Can Press.

Click here for Polar Presents: The Official Activity Guide and Other Free Resources Around the Web

IndigoKids Christmas Gift Guide – 2023

Chicago Public Library – Best Informational Books for Older Readers 2023

Starred Selection in CCBC’s Best Books for Children and Teens (Fall 2023)

The vast boreal forest spans a dozen countries in the northern regions like “a scarf around the neck of the world,” making it the planet’s largest land biome. Besides providing homes for a diversity of species, this spectacular forest is also vitally important to the planet: its trees clean our air, its wetlands clean our water and its existence plays an important role in slowing global climate change. In this beautifully written book, award-winning author L. E. Carmichael explores this special wilderness on a tour of the forest throughout the four seasons, from one country to another. Evocative watercolour and collage artwork by award-winning illustrator Josée Bisaillon provides a rare glimpse of one of the world’s most magnificent places.

With excellent STEM applications in earth science and life science, this enjoyable book aims to foster environmental awareness of and appreciation for this crucial forest and its interconnections with the entire planet. In a unique approach, the text features a lyrical fictional narrative describing the wildlife in a specific part of the forest, paired with informational sidebars to provide further understanding and context. Also included are a world map of the forest, infographics on the water cycle and the carbon cycle, a glossary, resources for further reading, author’s sources and an index. This book has been reviewed by experts and was written in consultation with Indigenous peoples who live in the boreal forest region.

Click here to download the free Teaching Guide for The Boreal Forest

Click here for The Great Big Boreal Forest Resource List, including a free downloadable activity guide.

Bank Street College of Education – Best Books of the Year 2021, 9-12-years-old

Chicago Public Library – Best Informational Books for Older Readers of 2020

Ontario Library Association – Best Bets of 2020

American Library Association – Top 10 Sustainability-Themed Children’s Books 2021

Forensic scientists study crime scenes, examine evidence, and invent new ways to solve crimes. Forensics in the Real World examines the history of this field, what forensic scientists do today, and what’s next for this branch of science. Easy-to-read text, vivid images, and helpful back matter give readers a clear look at this subject. Features include a table of contents, infographics, a glossary, additional resources, and an index. Aligned to Common Core Standards and correlated to state standards.

Imagine a time when video games did not exist! You might not realize that there was once a world without your favorite entertainment forms. From games and music to electronic television and downloadable movies, this title looks at major innovations in entertainment over the years, and the ingenious inventors, scientists, and engineers who made them. With a little inventive thinking, what might you create to help us learn new things, enjoy our free time, and connect with each other?

This title presents the history of forensics. Vivid text details how early studies of toxic chemicals and firearm analysis led to modern scientific crime solving techniques. It also puts a spotlight on the brilliant scientists who made these advances possible. Useful sidebars, rich images, and a glossary help readers understand the science and its importance. Maps and diagrams provide context for critical discoveries in the field. Aligned to Common Core Standards and correlated to state standards.

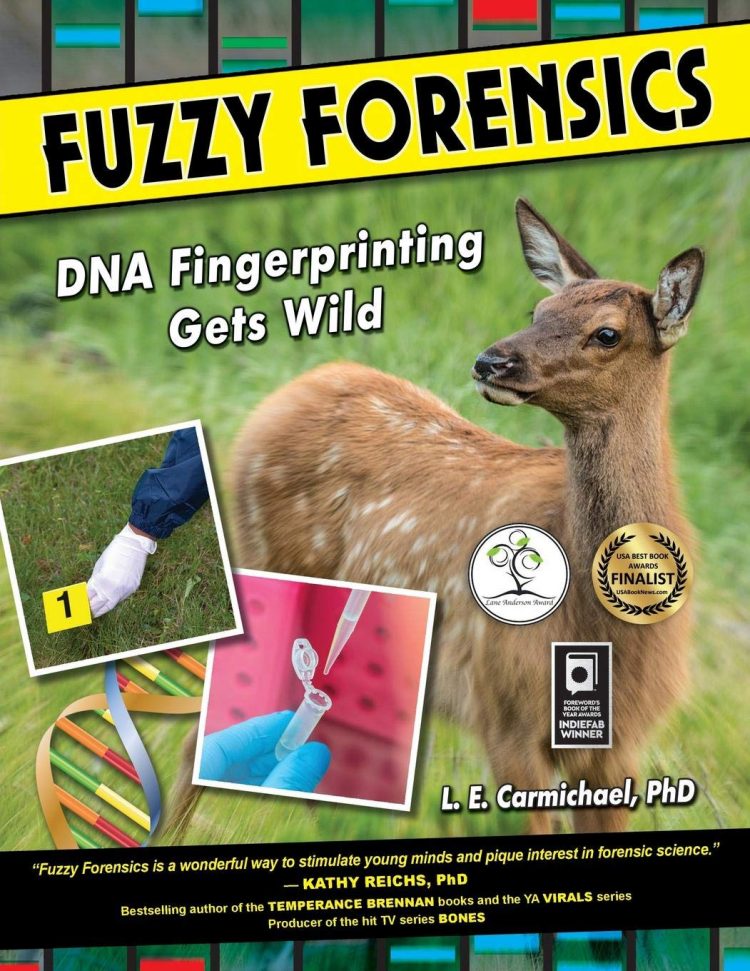

A wild elk and her calf, held behind the fences of a Canadian game ranch. Endangered parrots captured in the wild and sold as pets. African elephants butchered for the ivory in their tusks. In Fuzzy Forensics: DNA Fingerprinting Gets Wild, you’ll discover how witnesses, conservation officers, veterinarians, and scientists join forces to solve countless crimes against wildlife, all around the world.

Explore real cases that take you from the crime scene to the laboratory to the courtroom. See how scientists use DNA fingerprints to identify endangered species, match wild parents with their babies, or trace an animal victim’s home country. Become a wildlife detective by tackling four crime-busting experiments.

Containing vivid images, interviews with experts, and tons of hair-raising facts, Fuzzy Forensics will convince you that the only difference between solving human crimes and wildlife ones is the fur.

Note: Fuzzy Forensics has gone out of print, but used copies may still be available online.

Engineers design our modern world. They combine science and technology to create incredible vehicles, structures, and objects. This title examines amazing feats of civil engineering. Engaging text explores massive bridges, the world’s tallest skyscraper, and the Panama Canal. It also examines the engineers who made these projects a reality and traces the history of the discipline. Relevant sidebars, stunning photos, and a glossary aid readers’ understanding of the topic. A hands-on project and career-planning chart give readers a sense of what it takes to become an engineer. Additional features include a table of contents, a selected bibliography, source notes, and an index, plus essential facts about each featured feat of engineering. Aligned to Common Core standards and correlated to state standards.

Living with Obesity features fictional narratives paired with firsthand advice from a medical expert to help preteens and teenagers feel prepared for dealing with obesity during adolescence. Topics include causes and risk factors, complications, tests and diagnosis, treatment methods, coping strategies, and giving and getting support. Throughout the book, Ask Yourself This questions encourage discussion. Features include a selected bibliography, further readings, Just the Facts summary of medical facts about obesity, Where to Turn summary of key advice that includes contact information for helpful organizations, a glossary, source notes, and an index. Aligned to Common Core Standards and correlated to state standards.

Lindsey offers interactive science programs and writing workshops for students of all ages. Invite her to your school, library, or summer camp for an educational experience so fun, the kids won’t realize they’re learning!

Need a keynote speaker, workshop leader, or panelist for an upcoming event? Book Lindsey for a session guaranteed to inspire teachers, librarians, adult writers, or avid readers. Available for courses, conferences, and professional development days.

Lindsey has appeared at festivals ranging from Word on the Street, to Science Literacy Week, to Hal-Con. Check for upcoming events, or contact her to schedule a book signing or speaking engagement.

Happy Earth Week, my friends! Tech Support and I celebrated Earth Day by doing our annual "stick it in the ground and hope for the best" spring planting in the back garden. So far, the neighborhood bunny - affectionately ... Read More

I know I am a guest on a scientist’s blog today, but I have to talk about something that doesn’t quite fit in with scientific theory. Or does it??? Psychic powers? Synchronicity? Messages from beyond? Prophetic dreams? Dowsing? Far-seeing? Read More

Writing for children is an incredible experience and it’s also a lot of hard work. But, I love it. Not every single minute, but when I sit to write, I feel like I’m doing something worthwhile. I often pinch ... Read More