Welcome to STEMinism Sunday! As a former woman in science, I have a deep and enduring interest in the experiences and representation of women in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math). This series will be an opportunity for me – and you – to learn more about these intellectual badasses. Today, we’ve got a guest post from conservation biologist and children’s writer, Rina Nichols.

Welcome to STEMinism Sunday! As a former woman in science, I have a deep and enduring interest in the experiences and representation of women in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math). This series will be an opportunity for me – and you – to learn more about these intellectual badasses. Today, we’ve got a guest post from conservation biologist and children’s writer, Rina Nichols.

I have always loved animals and nature—and it was in my first year of university when I discovered that there was an entire field of science dedicated to conserving them, called conservation biology. That was also the year I read Dr. Goodall’s In the Shadow of Man for the first time. I was hooked.

I went on to receive a B.Sc. in Biology at Acadia University; followed by a graduate degree in Biopsychology (animal behavior) at Memorial University.

Then, for the next 18 years, I was lucky enough to travel to some amazing places across the globe like Mauritius (land of the ill-fated Dodo), the Caribbean, and Madagascar to study and help endangered species.

The goal of conservation biology is to maintain the planet’s biological diversity (biodiversity). So basically, it is a science born from the impact that humans have on nature. But it differs somewhat from other biological sciences because it is a crisis discipline. Meaning, sometimes conservation biologists must act quickly to help protect a species or a habitat before knowing all the facts (not ideal, but reality) – thus, it is a science driven by adaptive management.

Many of the ideas, techniques and methods used in conservation biology come from other biological fields including ecology, biogeography, ethology (think Jane Goodall!), systematics, genetics, evolution, animal husbandry, and veterinary science. It also incorporates social sciences like resource economics and policy, ethnobiology (the study of how different cultures utilize and treat living things), and environmental ethics.

To show how conservation biologists try to help maintain biodiversity, I’ll use one of my past field missions as an example.

This little creature is the narrow-striped mongoose or bokiboky (it’s Malagasy name, and yes for those creators out there, it’s pronounced bookie bookie). It is a small carnivore found only in Madagascar. The closest Canadian comparison would be our pine marten.

This little creature is the narrow-striped mongoose or bokiboky (it’s Malagasy name, and yes for those creators out there, it’s pronounced bookie bookie). It is a small carnivore found only in Madagascar. The closest Canadian comparison would be our pine marten.

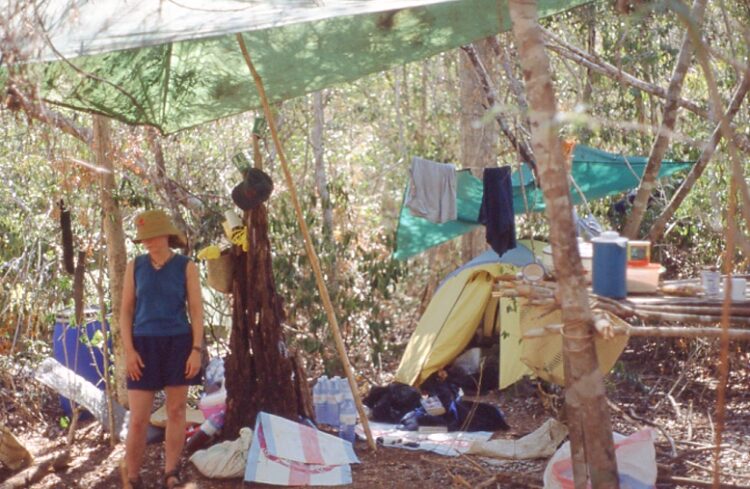

Studying the bokiboky was an adventure. I was part of a team of international and national biologists who traveled to the western coast of Madagascar and set up camp (a very rudimentary base camp) in a remote dry deciduous forest—in the middle of nowhere—to search out and study this elusive species. Only one other study had been carried out on the species way back in 1976, so there was a lot to learn. We set out live-trapping grids throughout the bokiboky’s suspected range and carried out mark-recapture sessions. For each captured animal, we recorded their age, sex, health condition, breeding status and collected genetic samples (its taxonomic status was unclear). This gave us information on the population size, distribution and demographics.

We also wanted to study what factors were impacting the population. Could it be habitat loss/degradation or invasive species or poaching? Was there something about the species’ biology or ecology that was making it more likely to be endangered? We conducted standardized habitat sampling and walked forest transects looking for signs of habitat loss (clear-cutting), invasive species and poaching traps. Then, we visited villages in the surrounding area and surveyed the residents to find out what they knew about bokiboky and talked with them about their experiences and their knowledge of the mongoose.

We also wanted to study what factors were impacting the population. Could it be habitat loss/degradation or invasive species or poaching? Was there something about the species’ biology or ecology that was making it more likely to be endangered? We conducted standardized habitat sampling and walked forest transects looking for signs of habitat loss (clear-cutting), invasive species and poaching traps. Then, we visited villages in the surrounding area and surveyed the residents to find out what they knew about bokiboky and talked with them about their experiences and their knowledge of the mongoose.

By using a combination of ecological studies, genetics, social science and traditional knowledge, we uncovered new information about the bokiboky population and its habitat status. It was this combination of information across many disciplines that allowed us to make recommendations to help conserve and protect them.

And since the bokiboky share their habitat with many other species (including the world’s smallest primate, Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur) these recommendations help preserve the biodiversity of the area.

And since the bokiboky share their habitat with many other species (including the world’s smallest primate, Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur) these recommendations help preserve the biodiversity of the area.

Today, I am not so much trekking through forests of Madagascar as I am writing at my computer, both reports and stories about animals for youth. I live in Guelph with my partner who is director of a conservation NGO, our two tween-aged boys who are animal lovers, a Newfoundland dog, a royal python, a milksnake and a bearded dragon. I’m a part-time environmental consultant but my favorite thing now is talking to kids about biodiversity and conservation. I supervise a weekly Wildlife Club at a K-8 school and I give classroom presentations.

During my school visits, I’ve met many of our next generation’s scientists and ecowarriors: kids who love exploring the magic of the natural world around them—asking clever questions about nature and creating innovative ideas and activities that help our planet. They understand, better than I ever did at their age, that the planet needs our help.