One of my weirdest experiences as a scientist was doing a maternity test on an elk.

One of my weirdest experiences as a scientist was doing a maternity test on an elk.

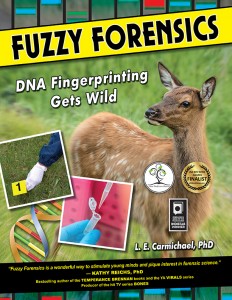

A female elk wearing a Jasper National Park ear tag had been found on an Alberta elk farm. Since it’s illegal to keep wild animals in captivity, that was pretty clear evidence of a crime. What was less clear was whether the calf she was mothering belonged to her. Wildlife officers said yes – the rancher had “kidnapped” two elk. The rancher said no way – that baby had been born to one of his captive elk, and legally belonged to him. A DNA test was the only way to find the truth.

I’m not going to tell you the answer, because if I spoiler my own book, they will take away my writer license. Instead, let’s talk about how – and why – adoption happens in the wild.

The how is actually pretty easy – it’s usually a case of mistaken identity. This can happen in herd animals like elk, where a lot of mothers and babies occupy a small space. It’s also been observed in polar bears. Two mamas came upon each other unexpectedly, and in the resulting scuffle, they accidentally swapped offspring.

Why is a bit less obvious. Central to Darwin’s theory of evolution is the concept of fitness. This is not a New Year’s Resolution thing. Nope, Darwinian fitness is a measure of how many of your genes make it into the next generation. In other words, parents with the most offspring win the race. So why would animal parents waste valuable time and energy raising kids that aren’t their own? Why would they help other genes succeed, at the cost of their own fitness? This altruistic behaviour doesn’t seem like the kind of thing that would survive natural selection.

When it comes to intraspecies adoption – adoption within species, as with the elk mystery – the answer is probably inclusive fitness, a concept developed by evolutionary biologist W. D. Hamilton. According to Hamilton, fitness is not about your kids, it’s about your genes. And your genes are shared by your nieces, nephews, and cousins, as well as by your own kids. So in a species like elk, where females in a herd are often related, it doesn’t matter so much which baby a particular female mothers. No matter what, she is helping her genes survive.

That’s all well and good, but what about cross-species adoption?

The internet is crammed with photos of mamas taking care of babies of entirely different species. Giselle (the dog) and Finnegan (the squirrel) are one example. Koko and her kittens are another. Most of these relationships develop in captivity, where natural selection is a lot less relevant. But it happens in the wild, too. In 1998, scientists watched song sparrows adopt a nest of yellow warblers, feeding and grooming them until they grew up and flew away. And in 2006, scientists described the adoption of a baby marmoset by capuchin monkeys. That case was especially interesting, because size and social behaviours differ pretty widely between the two species.

Since animals of different species are unrelated (except at really deep timescales), concepts like inclusive fitness can’t explain this behaviour. Adoptive parents pour time and energy into babies without any direct genetic payoff. So why would they do it?

Could it be that – gasp – animals have feelings? Some scientists think so. They believe that empathy is behind the adoption of a deformed dolphin by a pod of sperm whales. And that, perhaps, the lion who adopted an oryx (i.e. a food animal), may have lost her own baby and needed someone to love.

There’s very little information on adoption in the wild, so it’s hard to know for sure. But to me at least, it seems clear that these relationships benefit animals in ways that have nothing to do with survival of the fittest.