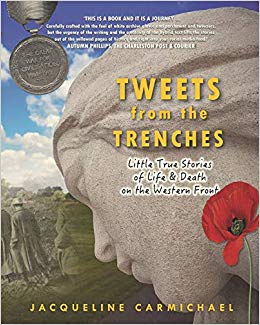

I’d like to welcome Jackie Carmichael to the blog today! In addition to being my not-so-evil-stepmother, Jackie is a journalist and a poet and is celebrating the release of her first book. Tweets from the Trenches was inspired by her grandfather’s WWI letters and trench diaries. It’s a potent, emotional gut punch of a book, and I highly recommend it to anyone interested in military or Canadian history.

I’d like to welcome Jackie Carmichael to the blog today! In addition to being my not-so-evil-stepmother, Jackie is a journalist and a poet and is celebrating the release of her first book. Tweets from the Trenches was inspired by her grandfather’s WWI letters and trench diaries. It’s a potent, emotional gut punch of a book, and I highly recommend it to anyone interested in military or Canadian history.

You can meet Jackie on October 22, at noon, at the Trenton Rotary Club (15 Creswell Drive, Trenton ON), where she’ll be reading and signing copies just in time for Remembrance Day. Take it away, Jackie!

There’s a pretty solid case to be made that our great-grandfathers (and great-great-uncles) used social media when they were in their teens and their twenties. A century ago, the equivalent of social media – texts, tweets, Facebook entries, and email – flew back and forth between friends and family and sweethearts, just slower.

No, there were no Steampunk cell phones, that’s true. But consider two billion pieces of mail posted from the Western Front in World War I. Between 1914 and 1919, notes scrawled on postcards, bits of paper, even telegrams and photos, were a social lifeline for young men who fought in places like Passchendaele and Vimy, and for the nurses who took care of them.

In a time that was equal parts boredom & deprivation, but many times sheer, horrific carnage and chaos, in pouring rain, they wrote while hunkering down under tin roofs in trenches, trying to keep warm while mortar shells whistled around them. They even wore fingerless “texting” gloves so they could hold a pencil in the cold.

On brighter days, in training camp, young soldiers littered the field, lying around, ignoring their friends, writing home to their parents with pencils they sharpened with their own pocket knives. All that was missing was a keyboard and screen. No email, no tinny voice messages on speaker or Bluetooth, no electronic “whoosh” when they sent them.

Technically, the original “twitter” came in the form of minuscule messages stuffed into tiny canisters and strapped to pigeon legs. The pigeons would then “home” to their portable mobile homes, bringing vital information about the battlefield to headquarters. In fact, the world’s first “drones” were pigeons set up with Go-Pro-like cameras strapped to their chests to get aerial pictures.

Technically, the original “twitter” came in the form of minuscule messages stuffed into tiny canisters and strapped to pigeon legs. The pigeons would then “home” to their portable mobile homes, bringing vital information about the battlefield to headquarters. In fact, the world’s first “drones” were pigeons set up with Go-Pro-like cameras strapped to their chests to get aerial pictures.

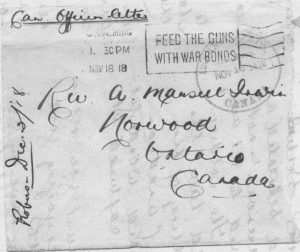

A letter from a soldier or a nurse would be collected at camp, tied in bundles with other letters, stowed in a crate and taken in the belly of a ship, which would then have to dodge German submarines (u-boats) to its country of destination, canceled stamps hanging on for dear life through onioned layers of handling.

Then it would join other North American mail to get shuttled on rail, loaded onto jalopies and finally tucked into cast-iron mail boxes or brass door slots.

And when the mail was received by some relieved person at the other end (“He’s alive!” they might say), there’d be no drop-down menu of “who should see this.” It might be pressed in a scrapbook, shown over tea or cradled in fingertips at the market, or maybe just saved in a drawer, in a bundle with a ribbon around it.

And when the mail was received by some relieved person at the other end (“He’s alive!” they might say), there’d be no drop-down menu of “who should see this.” It might be pressed in a scrapbook, shown over tea or cradled in fingertips at the market, or maybe just saved in a drawer, in a bundle with a ribbon around it.

So what if just one soldier had a #Smartphone a century ago? What if an ace could get a ticket for texting while flying? What if a doughboy could use GPS to get across the dark landscape of shell-holes that made No Man’s Land so hard to navigate? What if lads could snap selfies with shells literally photobombing their pics?

They’d have to set their phone on silent/vibrate when they slipped over the top lest a sniper hear and hone in on their heart. The ringtone of their generation: a brass band playing “When Johnny Comes Marching Home” {hurrah / hurrah} or the Colonel Bogey March, tinny from the depths of dugouts.

No, instead of checking for wi-fi, young men scanned for snipers. There is no Chrome History of the sites they visited, but in drawers and trunks and attics, amidst time-dulled medals, there are the analog equivalents of computer chips full of information. Fired by the lithium of memory, going a century with no need of a charging, gigabytes of old service records under layers of dust, like a paper copy last will and testament bequeathing to we heirs things that don’t die: The obscenity of war, the tectonic ferocity of a parent’s love. The abomination that is brothers dying before their grandmother.

And in these sepia-tinged memories, you can smell the TNT of what was given for country.

Hear the whistle of the shell’s arc in the storied clink of old medals.

Feel the panic slip in the mud underfoot.

#Hashtag that.

Jacqueline Carmichael is the author of ‘Tweets from the Trenches: Little True Stories of Life & Death on the Western Front.’ She will be visiting Trenton, Ontario from Oct. 18-22.